Enlarged vestibular aqueducts (EVA)

Enlarged vestibular aqueducts (EVA) are also known as:

- wide vestibular aqueducts

- dilated vestibular aqueducts

- large vestibular aqueduct syndrome (LVAS)

- large endolymphatic duct and sac syndrome (LEDS).

All these terms refer to the same conditions.

Enlarged vestibular aqueducts

© National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

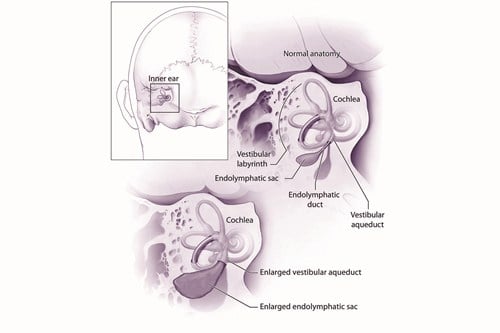

The vestibular aqueduct is a tiny, bony canal in the temporal bone which connects the inner ear to the brain cavity. It contains a fluid-filled tube called the endolymphatic duct and this connects the inner ear to the endolymphatic sac.

The endolymphatic duct and sac contain fluid called endolymph. The endolymph has a unique chemical composition and is essential for normal inner ear function.

In the early months of life the vestibular aqueduct is short and wide. It’s usually fully formed at around 3–4 years of age when it is narrow, long and J-shaped.

In children with EVA their vestibular aqueducts have not fully formed. They remain short and wide and, in turn, their endolymphatic duct and sac are larger than usual. EVA can occur just on one side but is often seen on both sides.

What causes enlarged vestibular aqueducts?

There are probably many causes of EVA but at the moment we don’t know what they all are. It can occur alone or sometimes happen as one part of a syndrome.

EVA is often associated with other structural abnormalities of the cochlea, meaning the cochlea didn’t develop fully before birth. An example of a structural abnormality is a ‘Mondini malformation’ (Mondini dysplasia) where the cochlea has fewer than the usual two and a half turns that make up its typical ‘snail shell’ appearance.

In some children the condition is caused by a change or fault in the SLC26A4 gene.

Your doctor may offer a test for this gene. Some changes in the SLC26A4 gene are non-syndromic and not thought to cause any other medical problems.

Other changes to this gene may result in Pendred syndrome. According to a study by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), approximately one-third of individuals with EVA and deafness have Pendred syndrome.

Another syndrome where EVA may be seen is branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome. A genetic alteration in the EYA1 gene causes BOR syndrome although there are other rarer genetic causes as well.

How are enlarged vestibular aqueducts diagnosed?

Children with sensorineural deafness may be offered a CT or MRI scan. A CT scan will show the bony parts of the ear and the vestibular aqueduct can be seen and measured. An MRI scan will show the soft tissues and fluids so the endolymphatic duct and sac may be recognisable.

EVA may also be associated with other deformities or underdevelopment of the cochlea and/or the vestibular (balance) organ and these will also be visible on the scan.

For further information on CT and MRI scans, as well as other medical tests used to help identify the cause of deafness, read our booklet Understanding Your Child’s Hearing Tests.

How common are enlarged vestibular aqueducts?

It’s not known how common EVA is in the general population but research suggests that most children known to have the condition will develop deafness. Around one in 10 children with sensorineural deafness have EVA.

What type of deafness do children with EVA have?

Children with EVA will have a sensorineural deafness that usually affects both ears but can be unilateral (affecting one side). Sensorineural deafness is permanent and most types are stable so that the hearing doesn’t usually change over time. However, in some children with this condition:

- their deafness may develop around the time of birth, in the early months or later in childhood

- their deafness may be progressive (gets worse over time)

- their deafness may fluctuate or change over time

- their hearing may fluctuate following relatively minor head trauma

- deafness, or changes to the level of deafness, may happen suddenly

- there may be a conductive (middle ear) component to the deafness which may not be the common, glue ear-type.

Does EVA cause any other difficulties?

EVA may also be linked with balance problems (known as vestibular dysfunction). Sometimes the semi-circular canals (vestibular or balance organ) are underdeveloped in a similar way to the cochlea. Some children may experience a feeling of dizziness and imbalance, particularly with minor head trauma; this may occur whether or not the blow has affected their hearing.

Other children may have very poor vestibular function (vestibular hypofunction), which makes it difficult for them to learn to do tasks that require balance such as sitting and walking.

However, the brain is very good at making up for a weak vestibular system, and most children and adults with EVA don’t have a problem with their balance on a day-to-day basis. Some will only have problems in certain situations such as walking along uneven ground in the dark.

Balance function assessment, safety advice and specialised physiotherapy may be helpful for children with balance problems due to EVA.

Read more about deaf children and difficulties with balance.

How does having EVA affect the hearing and balance?

Doctors don’t know exactly how having EVA affects the hearing and balance. The most widely accepted explanation is that rapid fluctuations in pressure in the fluids surrounding the brain result in abnormal transmission of these forces through the vestibular aqueduct.

This in turn causes pressure on the delicate membranes of the inner ear, leading to possible damage to the tiny hair cells which convert sound (in the cochlea) or movement (in the semi-circular canals) into the electrical signals which the brain uses to make sense of sound and movement.

These changes in intra-cranial pressure (pressure inside the skull) could be caused by head trauma such as a knock to the head, strenuous exercise, vigorously playing woodwind or brass instruments, or changes in atmospheric pressure such as flying in unpressurised aircraft.

All deaf children should be offered regular hearing tests. This is likely to be every three months during the first year they wear hearing aids, then every six months until five years of age. From five onwards, they will have annual tests until they leave school.

If you notice any changes in your child’s hearing levels in between appointments it‘s important to let your audiologist know. Sometimes children with EVA will have sudden drops in their hearing levels. The hearing may return to its previous level, or there may be some improvement to a new ‘normal’ level. Hearing levels may therefore follow a gradual ‘step-by-step’ deterioration over time.

Hearing aids are very effective for deafness caused by EVA. It’s important that they are regularly programmed to take account of any changes to the child’s hearing. Some children with severe or profound hearing loss who don’t benefit fully from conventional hearing aids may benefit from cochlear implants.

Glue ear is a very common childhood condition that can cause temporary conductive deafness. A child with EVA may also have glue ear which may make their hearing levels temporarily worse. It’s important that the audiologist takes this into account when programming your child’s hearing aids to make sure they’re not disadvantaged while they have glue ear.

Your local audiology and education services should provide support for you and your child. Your audiologist will refer you to a Teacher of the Deaf who will be able to help you with lots of issues related to childhood deafness, such as communication, use of hearing aids and other technology and choosing a school.

They’re also responsible for making sure your child has the right support in place at school. You may also be offered an appointment with a speech and language therapist.

Precautions and prevention

Not every child with EVA will have fluctuating or sudden drops in hearing levels. This means that each child will react in a different way to minor head trauma. The hearing of some children may be completely unaffected where another may have dizziness, tinnitus and/or fluctuating hearing.

You’ll need to think carefully when making choices on behalf of your child when they’re young; weighing up the need to protect them from the risk of any knocks to the head or changes in pressure, with allowing them to take part in normal childhood activities.

Ultimately, you’ll only know what will affect your child after it’s happened. We advise you to be cautious, even if your child hasn’t had any problems caused by head injury. Make sure you make decisions with your child’s schools about which sports and activities they can participate in (this may vary depending on your child’s previous history of fluctuations in hearing).

Your child should avoid activities where risks of blows to the head or increased pressure on the inner ear are certain or very likely, including:

- contact sports, such as kick-boxing, boxing, ice-hockey and rugby

- scuba diving

- go-karting/quad biking

- snowboarding

- bumper cars/roller coasters

- weightlifting

- bungee jumping.

When activities may result in a blow to the head but aren’t considered inevitable then you might want to allow them to take part wearing the correct head protection (e.g. scrum caps, helmets, etc.):

- football, netball, hockey, squash

- cycling

- horse-riding

- sailing

- gymnastics.

Activities that are generally considered low-risk include:

- swimming

- snorkelling

- trampolining.

For some children with EVA swimming underwater can be dangerous. These children can become disorientated under water because they don’t know the right way up. All children with vestibular hypofunction must always swim with someone who knows about their difficulties. If your child has poor balance we suggest you discuss the issue with your doctor for advice about safety.

Support at childcare or school

All deaf children are entitled to additional support at school to help them access learning, however if your child has EVA you might like to think about other types of support they might need for their condition.

You might want to think about if they’d benefit from:

- additional classroom support, such as a classroom assistant, to both help them access the curriculum and avoid tumbles and knocks

- playground or lunchtime/break assistants to make sure they’re not getting hurt at break and lunchtimes

- an Education, Health and Care (EHC) plan, individual education plan (IEP) or coordinated support plan (CSP).

As your child gets older, think about:

- finding a balance between your child’s emerging independence and the need for caution in play activities

- encouraging your child to take responsibility for their behaviour

- how or whether your child can take part in sporting activities.

When they reach their teens, think about:

- teaching them how to take responsibility for not putting themselves at risk, for example, by not sitting in a place where there is an increased risk of getting hit on the head

- making sure they understand the importance of choosing which sports and activities they take part in carefully, and if they do, wearing head protection

- discouraging them from taking part in activities that could be dangerous, such as riding a motorbike.